Interview with John Paul Ricco on The Collective Afterlife of Things

In July 2019, Sarah Pereux, an undergraduate at the University of Toronto, Mississauga, interviewed me about one of my current research projects and advanced undergraduate seminars: “the collective afterlife of things.” Below is a slightly edited version of the transcript of our conversation, in which we discuss art, extinction, capitalism, and ecology. The published version appears in FORGING, the sixth and final broadsheet by Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge (SDUK)—Issue 06: FORGING available in print and online.

We need to understand global financial capitalism as an ecological force of extinction.

What began and continues to fuel your interest in this topic?

JPR: There are a number of things that motivated this interest and they are of a variety that corresponds with the diverse and multifaceted nature of the problem that I am trying to address. It’s not one single thing that brings me to this project, and this is because what I refer to as “The Collective Afterlife of Things” is, itself, not one dimensional but concerns a complex configuration of issues pertaining exactly to those points where art, aesthetics and eco-ethics; and the inanimate and extinction, might converge. One source has been my ongoing interest in the relationship between art and finitude; art and ends; finality, disappearance, withdrawal, and absence. This is sometimes thought to be a negative aesthetics, although I don’t think about it as negative in any conventional or definitive sense. Rather, my work over the last 30 years has been dedicated to thinking about the relationship between art and loss, and how art can be a means of contending with that loss, but in ways that are not redemptive or mitigating, or part of some sort of reclamation project. Meaning, a conception of art as that which is not trying to preserve and retain what has been lost, but instead is a means of staging, affirming and underlining the fact that something has been lost.

SP: So, it’s not about fixing it, but about recognizing that loss.

JPR: That’s right. And how does art, film, literature, poetry, etc. understand and present loss as precisely that which cannot be presented? In a sense, it’s about how art can be faithful to loss by allowing loss to be lost and not regained or recuperated.

For instance, in the mid-90s, I did a curatorial project called Disappeared, that was about art and AIDS. It was an exhibition that brought together eight (or maybe more) contemporary artists whose work, each in its own way, was attesting to death and disappearance caused by AIDS, yet in ways that weren’t recuperative. The art wasn’t representational, and it wasn’t memorializing in the conventional ways in which memorial happens. Instead, the art in the exhibition was confronting us with the physical, visual, perceptual, and architectural materiality of that disappearance.

So, I developed this notion of disappeared aesthetics, as a way in which art and aesthetics can speak to this fact. But this is not necessarily unique, it is something that I am also learning from 20th-century continental philosophy and 20th-century art history, in which a number of different thinkers and artists have themselves— even prior to this history that I am engaging with—tried to think about writing absence, writing what cannot be written. In the work of Maurice Blanchot for instance, it’s what he calls “the writing of the disaster.” So, you can see how, in a way, one can update the work of my predecessors and my own work from over 20 years ago, and connect it to our current context and issues of climate change, global warming, environmental devastation and the kind of disasters we are contending with today. And yet still ask the question of what is the place of art in that context, what does it enable us to do? So, part of the answer to the question of what began and continues to fuel my interest in this project, is this longstanding question about the relationship between art and death, art and finitude.

The seminar course is not an introduction to art, art history, and ecology. It is not an introduction to eco-aesthetics or anything like that. It works across those fields and domains but in a very specific way. The course is putting forth an argument about art and extinction. It’s my argument, it represents my particular theoretical and critical take on the relation between art and extinction. You might say that the course is biased because it is so particular in its focus and argument. The course introduces you not to these broad fields, but over the course of twelve weeks it introduces you to the major points of the argument. In a way, the argument is divided into twelve parts, and it doesn’t come together till the end. This is how I often teach advanced-level seminars. The course then, is putting forth an argument and it takes you through that argument step by step. Yet it still keeps open the opportunity for everyone involved to critically question and grapple with the argument and to find their own path.

SP: Well that’s great for your own research as well.

JPR: Yes, exactly. My intention is that over the twelve weeks of the course this fall term, I can write the first draft of the book on The Collective Afterlife of Things. This is the third time I am teaching the course.

SP: Does it change every time you teach it?

JPR: Oh yes. It is constantly being revised and adjusted. Things drop and other things are added based on new work that has been coming out and new turns of events. It’s surprising the number of great changes that have happened since the first time I taught the course two years ago in terms of ecology and the environment. And the course tries to respond to those things.

Your research uses the term “things” in a very broad sense. Can you define what you mean by “things”? And, why is thinking through these “things” useful for analyzing our current issues?

JPR: Within this context, the term “things,” is deliberately being used in place of image, object, even subject. I would say in its definitional and referential sense, “things” encompass material and physical objects, but subjects can also be things when they are seen or used or cared for in certain ways. In this regard bodies are things, they are corporeal things, but there are also incorporeal things. These incorporeals are no less real or affective than corporeal things.

SP: Can you define incorporeal?

JPR: Incorporeal is that which does not pertain exactly to the corporeal, that is, to the physical or bodily, but still has an intimate and inextricable relationship to the corporeal and the bodily. This could be something like a sense or sensation where it’s not so easy to locate it in the physical corporal body, yet it is something that the body has a relationship to, can be affected by it, and so forth. There are other ways of thinking about incorporeals, such as concepts or even words. “Things” that don’t take on a physical corporeal body, but still exist in a relationship to such things. Thinking in this way is just an attempt to open up to a more expansive notion of things, that is not necessarily simply reducible to objects.

Objects are a particular kind of thing, but I am trying to say that there are many different kinds of things. Descartes famously divided things into things that are thinking, he called them in the Latin phrase, res cogitans—things that think. And things that are extended spatially, he called them res-extensa. So, the thinking thing and the extended thing. And since then, continental philosophy has been interested in complicating this distinction and rendering a less definitive and stable relation between thinking things and extended things, and part of that has to do with an attention to the way in which the thinking thing is also an extended thing. The famous Cartesian mind-body split has been problematized, in which thinking things are understood to be extended things. And maybe extended things, even if they are or aren’t thinking things (a stone or tree) might still have other means of communicating or having a rapport with the world. These are age-old philosophical questions about what is living and what is not, what has a world and what doesn’t, and what is the difference between the animate and the inanimate.

This becomes really important in the context of my project and our discussion, because we are needing to think beyond the nature-culture divide and to think ecologically about relations between the organic and the inorganic, the animate and the inanimate, the human and the animal, the geologic and the fleshy. In my work, and in the work of so many others, the thinking thing is always an extended thing, and our attention to extended things liberates us from an overly anthropocentric or anthropomorphic perspective.

There are natural things, there are artificial things, there are technological things and technological things often make it difficult to distinguish between the natural and the artificial. Sometimes that’s what the technological thing is meant to do: to blur that distinction between the natural and the artificial. There are conceptual things, there are linguistic things, visual and invisible things. And as contemporary physics tells us, there are things that we can see but do not know, and there are things that we know but have not yet acquired the means to see. I’m thinking about, for instance, in astrophysics, the understanding of dark matter as that which probably constitutes the majority of the universe. We are able to name it, but we haven’t been able to see it, it may not even be matter, but it’s something with which the universe is largely constituted. But we do know of it based on what does exist, in the way that we know that there is a lot other stuff beyond what we do know and can measure, and physicists call this other stuff dark matter. I’m interested in this.

SP: This idea of expansion is an interesting way of thinking. And thinking through these things and changing our way of just limiting what we think they are, you are learning to think about things differently and to see the world differently.

JPR: That’s right. If you are saying that there is an interest in working at the limits of knowledge and vision. Working at the limits of definitions and concepts, that’s certainly what we are talking about here. That’s what it means to advance knowledge and understanding. That’s what I think it means for thinking to operate at the limits of intelligibility. This is not easy, it’s its own kind of rigorous exercise. And so as students being called upon to do that—which I think is absolutely the project, the purpose of being a student—you are being pushed to really think beyond the conventional or typical ways of framing things, and to think about things maybe even beyond a certain problematizing, a certain familiar problematizing of those things. It’s even further than that, it’s really pushing at the limits.

So the point here is that if we are taking what we call an expanded perspective—which is not as Donna Haraway (an important theorist in the field of science studies and feminist ecology), will say, definitely not the god trick, the omniscient transcendent point of view—when we are talking about an expansive field of perception, we are talking about a more eco-cosmological approach. In that sense, in such an eco-cosmological approach, the human, life, and bios are only a tiny fraction of what constitutes the eco-cosmos. Therefore, these things should not be able to determine our thinking and engagement with the world. This is always a humbling affect when it comes to the eco-cosmological. A perspective that says, first, “it’s not all about you,” and second “get over yourself because there’s a lot more going on out there” and third, “you will never really know or be able to grasp it all, and yet you still have to contend with that realization as a person and as a thinker.”

The concept of legacy can influence how we act and think about the future, in order to feel like we are marking our presence within this world. When discussing topics of extinction and “endings,” what role does legacy play within your course? How do you approach thinking about individual or personal histories?

JPR: This is really important. I take legacy to mean the ongoing effects, values, and importance accorded to one’s words and deeds by others and for others in the future. Beyond one’s own life and death. That’s legacy. But with the notion of legacy may also come the notion of immortality. That is, of the ways those same words and deeds that we are talking about, can survive our mortal selves and thereby transcend our existential finitude, the fact that as beings we have an end. Which we refer to as death. Beyond that it’s hard to say.

In fact, thus far we know of no existent that in its being exists eternality; that is not finite but infinite and not just infinite, but eternal. In this exercise of conjuring up what such a thing could be, civilizations have come up with figures and names such as “god” as that something or someone that transcends finitude, time, and space. But everything else that (really) exists has such an intimate, irreducible, irretractable, and unavoidable tie or relation to finitude, and to an end. This is why when we are thinking politically, ethically and aesthetically, some of us might want (and this returns to the opening of our conversation) to think about that relationship to ends and disappearances. Because if finitude is what defines being, then it’s fundamental—we say it is ontological. In that regard, finitude is not something we can avoid or think we can overcome.

We can then take this further and talk about extinction, and the way in which, ultimately, those existents can then be grouped collectively. Whether we are talking about bacteria, dinosaurs, or the human, all will eventually become extinct. We know of those existents that have, and we can assume that every other thing that exists will become extinct at some point. What I’m interested in exploring in my work, is the fundamental connection between extinction and existing. To tie those together, because I believe they are inextricably—ontologically—tied together.

SP: I guess that brings up a different feeling of loss. A loss of the idea of leaving a personal history behind or somehow accepting that once you’re gone your gone.

JPR: Yes, there is a sense of your own mortality. And out of that comes an interest in one’s legacy, in that which transcends one’s mortality and might render one immortal. In that way, art has been thought of as being a means in which the subject, the artist, can render him or herself immortal. That is, by artists making things that will transcend their death and that might continue to be considered valued, that will be preserved, collected, looked at, and thought about, far beyond the artists’ lifetimes and their deaths.

On top of that, we might introduce the moral philosopher Samuel Scheffler’s thesis about the collective afterlife, and this is what first inspired my notion about the collective afterlife of things. Scheffler a few years ago gave a series of honorary lectures that he titled “Death and the Afterlife.” It seems today that there is a lack of confidence or a lack of assurance, on the part of many people about the long-term survival of humanity. One might argue that this is an historically unprecedented phenomenon. Even if we can think back historically to various other apocalyptic visions, there is something unique about this one, because it is not just anthropocentric, it is ecological. It pertains to the relationship between the human and the environment. This relates to Scheffler’s interest in the moral and ethical stakes that would accompany the absence of this lack of confidence in the long-term future of humanity. His proposition is that human beings act in moral and ethical ways and pursue many projects that are tied to and emerge from this shared commitment to each other, based on a deep and unquestioned sense or belief in the long-term existence and survival of humanity for millennia to come. What he is saying is that even though conventionally we think we are much more concerned with the afterlife of ourselves and our friends and family, what actually guides our ethical and moral actions is some implicit sense that we carry with us: that there will be humans for a very long time. He says, take that away, and moral purpose might go with it.

SP: Well that changes how you will live your life.

JPR. Yes. and there’s a distinct possibility that we will also be without one of the principle perspectives that informs and shapes and guides our ethical commitments. He will ask, for instance, if you are an artist and you know that in 30 years there will be no more humans would you continue making art?

SP: I would.

JPR. The question would become what kindof art would you make and what would motivateyou? If you know that no one would be around to see it, thirty or more years from now. These then become questions that inform the seminar and the courses’ interest in art and artistic practice in the midst of what is called the sixth extinction. So how would art respond to this “no future” thesis? What would it do if there is no longer a sense of the long-term future of humanity—and I think this is less of an ifthese days, and more of a question of when. What role will art play? That is, of course, if you say “yes” to the prospect of still doing something, and do not throw your hands up in the air and give up. This is what the course and this project is asking. How can art contend with that lack or absence of confidence in the long-term future of humanity and many other species, when it seems as though the history of art has been predicated upon that very sense of futurity?

How can art contend with that lack or absence of confidence in the long-term future of humanity and many other species, when it seems as though the history of art has been predicated upon that very sense of futurity?

SP: I think there wouldbe an interesting shift from making art for others to making art for yourself. You would be left with confronting yourself.

JPR: The answer that many people will have is that “I will continue to do things, but they will be for my own sake”. The question then becomes: does this lead to a notion of art for art’s sake? Or art that is very personal. Maybe. I’m not going to advocate for that, but that could be one possible response.

SP: Well it will shift the role of art as a way of thinking about the world and responding to social and political events. And its role of sending a message. Art has an active part in the community.

JPR. That’s what we are asking, what role will it have in these circumstances.

SP: It can be anything.

JPR: One of the frames we will use to think about this, is in terms of terminality—the condition in which something is understood to be terminal. In the seminar, we will read a wonderful essay by Sarah Ensor on terminality, which we take terminality to mean the prognosis (we can use medical language here), the prognosis of an end or of impending death. But there is almost always no way to go any further or to be more definitive as to when that end is going to come. We know that when it comes to certain forms of terminal cancer and so forth, someone is given a diagnosis, “the cancer is terminal you are not going to survive this”—now maybe medicine is advancing and maybe it can predict such things a little more accurately—but there are always cases where someone says “wow I was only given three months to live but I’m still alive a year and a half later.” That’s the terminal phase, that’s the temporality of an existence that occupies the end in an open-ended way, and in a way that is not definitive.

That’s the kind of temporal zone in which we might be inhabiting as a species right now: we don’t know how long this terminal phase is, or what is going to survive it. It’s not a definitive end, as though it is already all over, nor is it a prediction of when the end will actually happen. Instead it is the sense of an ending without anything more definitive than that very sense. Just as in that medical case, the patient does not give up on living, since there is still living to be had, to be done. The same question arises: what does one continue to do with one’s time? Maybe it’s something like the cliché of “live everyday like it’s the last day of your life.” What would be (will be) the legacy of humanity? What would we leave to the world? Do we need to leave works of art? What kind of works of art should those be? That’s what we are asking. We are asking, collectively, how we think about the afterlife. And how do we think about things. Art is a thing. What form of a thing should it take? Does art have to be a material, physical thing? Should we be leaving more stuff around, or what might those remains look like?

How does art, film and literature function as a tool for thinking about the realities of climate shifts, the afterlife, and the apocalypse? Why do unfinished works play an important role in this analysis?

JPR: The unfinished is a key example of this modality of the terminal in which the work itself and one’s engagement with it, one’s partaking in it, is about acknowledging and affirming that terminality. The sense that the work is on the verge of disappearing, unless there is an ongoing engagement for generations. That has always been the case. In fact, one way to define the work of art is as that thing that has been made, and has been considered valuable, and that we want to preserve for generations to come. This distinguishes a work of art from any other thing that we don’t keep or that we throw away. Again, what I am interested in, is how a work of art is operating through the logic of the unfinished. If the work of art has extinction “built into it,” disappearing and thereby operating through withdrawal and retreat and erasure, and the work is calling upon us to keep that it alive, to keep it dying (so to speak), to keep it withdrawing. Perpetually to keep it on the verge of its disappearance.

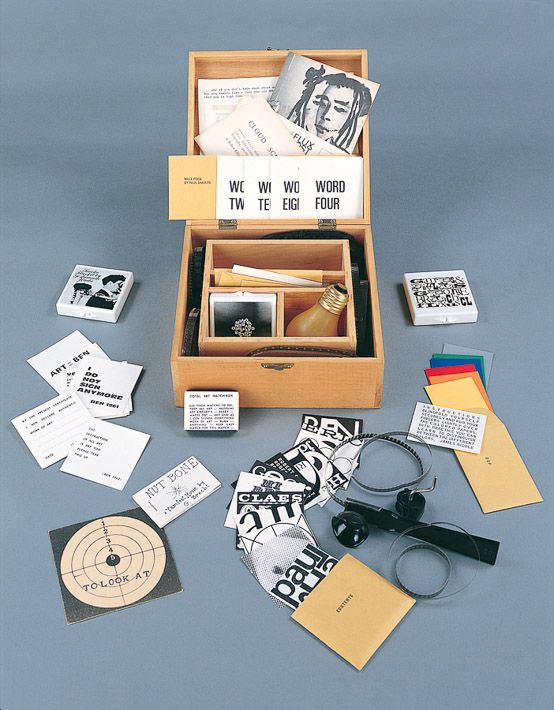

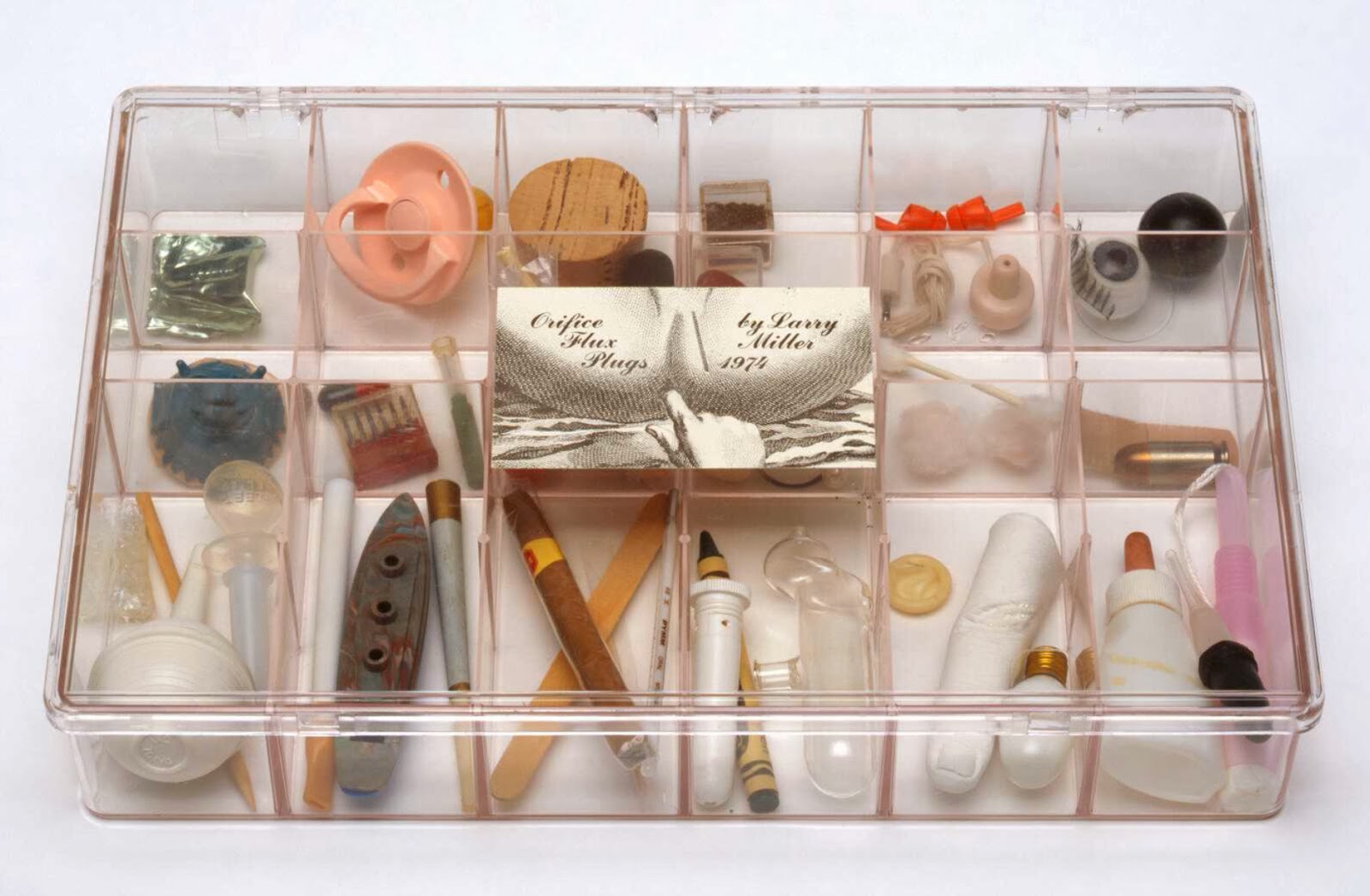

Here is the perfect example—and again I will refer back to earlier work that informs my current project. Even though his work wasn’t in the Disappearedshow, the work of Felix Gonzalez-Torres is a key example of exactly this kind of unfinished and inoperative art. His art operates through an aesthetic logic of withdrawal, that I argue ethically calls for us to decide to participate in that withdrawing. If you know his work, especially the paper stacks and the candy piles, there are a number of sheets of paper or pieces of candy presented in the gallery setting, and someone engaging with the work is given an invitation to take a sheet or a piece. In that participation, the work is disappearing. It is a process of loss. The work stages and enables the performance that an innumerable number of people can participate by taking a piece. One might say, to un-make the work.

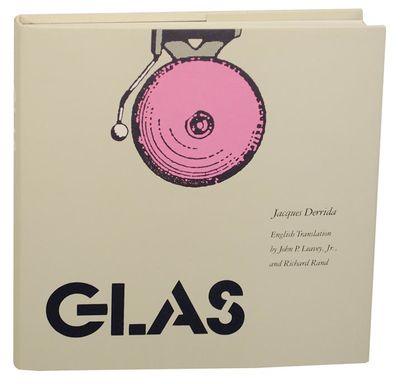

We typically understand artists as makers, but through the history of conceptualism there has been the notion that the artist need not be a maker, and this goes back to Duchamp and the ready-made. He didn’t have to make those things, he found them already made, he just had to appropriate them and place them into a different context. So that completely changed the concept of artistic practice. No longer was the artist necessarily a maker of things, but instead could have a conceptual relationship to things, or the work could consist of an encounter to something, a thing, a ready-made.

It was Duchamp who said, “the audience completes the work,” he as the artist does not complete it. What I argue in regard to Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s work, is that he takes this Duchampian paradigm a bit further, and in a sense says: the audience incompletes the work, they un-finish it, and render it unfinished. That stack of paper and that pile of candy are unfinished, meaning they are not a whole single or permanent thing, these works literally are coming undone. I argue that the finishing of the work lies— in its un-finishing—that we, collectively, are invited to partake in.

This is one way in which I’m thinking about or understanding what it might mean to talk about the work as having extinction built into it. Basically, the work puts you in relationship to the collective afterlife of the work, and the things that constitute it, and in a way that opens itself up to its un-finishing. The fact that it could disappear and the ways in which you’re being put into a relation with that disappearance, here in terms of ordinary things. It makes us think about those everyday mass-produced products that we rely on day to day.

SP: It makes me question what happens to the art when we are extinct, and we cannot participate in either role.

JPR: Exactly. It is asking about what we collectively and individually are leaving behind. Thinking ethically, politically, and ecologically, we should be thinking beyond our individual selves. We should be thinking about the impact we have on others, and that we are always in relationship to others.

SP: It also makes you think about roles. Who gets to fill these roles? Who gets to be the ones who takes the candy and who replenishes it?

JPR: Yes, and I think the hope that through these artistic or aesthetic practices we can become attuned to how these things should not be exclusive to one person or group or type of work. That they call our attention to the very basic and fundamental relationship that we have collectively to things and their afterlives.

SP: It’s kind of interesting how the artist kind of disappears from this relationship altogether.

JPR: That’s right. That has been an interest and a guiding motivation of aesthetic practice since Duchamp, and what Roland Barthes called “the death of the author.” This, against the modern notion of art, in which artistic subjectivity has been treated as the means to understand a work as where the work gets its meaning, its source and its importance. Including the valorisation of the artist and the artistic genius and so forth. But this is also putting into question the notion of the autonomy of the work of art. As that thing that can exist independently, as something that is self-sufficient and self-explanatory, and that finds its meaning in itself. Instead, we are interested in the dismantling of modern aesthetics and the notion of the artist, in order to move toward a notion of something that is not individual—either in terms of the artist or the work—but is collective and that needs constant caretaking and decision-making as to what to do with this thing (this work), and why it continues to matter, and what role it plays in our shared lives going forward.

When confronting the Anthropocene and the effects of climate change, the process of decolonization becomes a large factor when addressing our future. How does your background in queer theory influence how you think about decolonization and the topics of this course?

JPR: Where my work in queer theory meets up with this question of decolonization is in terms of non-appropriating relations to things. If we understand colonization as a process of appropriation in which what is being appropriated is not always territory and land, but often language and mind and hearts, then we have to think about how decolonizing or non-colonizing relations to things are ones that are committed to or that operate through non-appropriation. And what my work in queer theory has been almost entirely interested in, are these non-appropriating relations to people, places, and things—forms or modes of rapport that are not about having, claiming or occupying in any extended or permanent way. With this comes an argument about the pleasure of sustaining the inappropriable. So much of capitalist and consumer society is about finding pleasure in satisfying one’s desire in things that one can own or possess. And I am interested in making a counter argument about how one can derive tremendous pleasure from a relationship to things that cannot be appropriated or that you do not appropriate. That you do not colonize or claim as your own.

Something like cruising for sex and other such hookups—which is much of what my first book Logic of the Lure is about—is an example of how one can be out in the world in such a way that you can have meaningful relations with people, places, and things that do not require laying claim to them permanently. Sometimes what follows from that, is the sense that two or more people can come together and have a meaningful relationship, and yet at the same time that relationship does not have to be sustained indefinitely and can be such an encounter that it doesn’t leave a trace.

We know from an ecological view that the saying “leave no trace” is a guiding principle of being outdoors, but it can also be a way of thinking ethically and politically in everyday practices in which you can move through a space, connect with others, without leaving a trace. Thinking about this in terms of art, art is one practice that relies on making traces. Is there a way that art can also participate in this meaningful collective rapport with people, places and things, yet in ways that it does not claim permeance? Performance art has been committed to this, as well as other art forms that are not about materiality but the immaterial. Conceptual art has bestowed to us some understanding of this.

Further for me, intimacy (my current book project is called “The Intimacy of the Outside”), intimacy is the name for this rapport with the world that does not operate via the will-to-possess. Intimacy is not possession, it is not claiming the other, nor is it even a joint claiming of each other. Intimacy is this rapport with a lack of will-to-possess. This would be a rapport with the world, and with the Outside as something that is inappropriable, something that cannot be appropriated by oneself, or by the other, or by any group.

Intimacy is not possession, it is not claiming the other, nor is it even a joint claiming of each other. Intimacy is this rapport with a lack of will-to-possess. This would be a rapport with the world, and with the Outside as something that is inappropriable, something that cannot be appropriated by oneself, or by the other, or by any group.

SP: I’m trying to tie this to thinking about the future. And how we cannot possess things but that we can no longer possess the future.

JPR: Well I think that ties into your next question.

Using the word “collective” suggests a shared understanding of the future, or a shared future reality. But when we talk about “our” future, who are we talking about? How can we account for difference and experiences of oppression or marginalization in imagining a collective future?

JPR: One way of thinking about this collective sense of futurity would be based upon a collective and fundamental sense of uncertainty and inappropriability of the future. That is not exactly how things work or are thought about these days, but that doesn’t mean that that sense of uncertainty and inappropriability doesn’t exist.

This sense is there, but it is suppressed because people might otherwise be frightful or fearful of that uncertainty. This is where faith or belief or a religious type of afterlife might come into play. That you even need to appropriate that which has yet to come. It doesn’t even exist yet, and you are already laying claim to it. That’s the appropriation of the future. What that means is the seizure of what has yet to happen, so you are already closing down the possibility of it happening otherwise, and you are foreclosing the possibility for other life-worlds to be created. This is what capitalism does, it appropriates the future. It’s always ahead, it creates a desire for a certain kind of future, it creates images of that future that motivate people to want that future, and to work towards that. It is happening at a very accelerated rate, and this is sometimes called progress even when it is not.

If there is a shared sense or understanding of the future that is experienced on a collective level it is something like a profound and undeniable sense of uncertainty. I think this is undeniable, even though many people try to deny it. Here I think we return to Samuel Scheffler and his thesis on the collective afterlife. About the confidence that humanity shares in its long-term future. Except that at the moment, and thanks to a number of major shifts that are political, geo-political, ideological and ecological, that sense of confidence has been compromised and sometimes feels like it is entirely absent. In other words: that there is no future. But this doesn’t mean that nothing no longer matters, and that we can resign ourselves to some sort of nihilistic attitude. What I think it means instead is that without such implicit or unquestioned assurance about the future—if we don’t have this—we cannot take the future for granted as though it is pregiven. But instead we need to create it. What I am interested in, is how art, literature, poetry and film can be part of this creation, while not operating with the usual desire for longevity and immortality but instead in terms of its own sense of terminality. Terminality is its own sense of an ending.

We are asking about that zone or space between a future for millennia-to-come and absolute doom. Why are those the only options when thinking about the future? Could there be a more realistic and different way of thinking about futurity? Neither as infinite nor as absolute ending, but as open-ended. Opening the end as the work that we are responsible for. The ethical and political responsibility comes from never losing site of terminality, of that finitude, and that sense that things do disappear and die. How do we contend with that, and how does art respond to that fact? Nothing lasts forever. Extinction is a force that moves through existence.

In terms of the second part of your question, “when we talk about our future, who are we talking about?” this is exactly what I was speaking to a moment ago in terms of an impossible totalization. This is also about a claim of the future. The inappropriable is a way to claim in a way that does not claim. That does not possess or operate with the will to possess the future. Just as the future does not belong to any one person or group, it also cannot be claimed in any imagined collective totality. Both of those are extremely destructive moves. In the name of one or in the name of all, both are exclusionary. Even though the name of all seems to suggest otherwise.

For instance, in thinking about art and even in thinking of one of Felix’s paper stacks or candy piles, I am interested in the way in which the innumerable or that which cannot be counted—the fact that those things characterise the multiplicity of things in the world. I’m interested in the way that they do not add up to some kind of single whole. This is very much a philosophy or politics that is sometimes referred to as the philosophy or politics of difference, but whether or not we use that language, it is certainly about the parts that only exist has parts, that are not part of some greater whole. It severs that relationship between the part and the whole.

The world is made up of parts and there’s no way of bringing all of that together into a single whole. Instead, this is about a parceling of the world, which is not the partitioning of the world, but the affirmation that the world only exists in its parts and singularities. The political question arises as to how this parceling takes place, how are things distributed, and how one can or cannot be allowed to partake in this.We are back to Felix Gonzalez-Torres and his work, which in a way is an allegory of who gets to participate, to take a piece of candy, and who doesn’t. What does it mean to take that candy? What does it mean to appropriate that piece of candy? What does it mean to lay claim to it? What do you do with it once you have it? Why would you take it? Would you take more than one? How does all that taking amongst others…does it ever become something singular or unified? It is an allegory for all the things in the world that people are partaking in and laying claim to.

How then to think collectively about the afterlife of those things and to allow these questions about the afterlife and finitude to inform your very decision to take? What does it mean to participate and how would you do it differently than simply in terms of the will to possess and your will to secure your future? Could there be a way in which you could do things differently, such that the practice of politics and ethics would be one of un-finishing the future?

Could there be a way in which you could do things differently, such that the practice of politics and ethics would be one of un-finishing the future?

SP: If the world is made out of parts, and there is a consciousness of being one of those parts, such that you are thrown into certain political and social parts when thinking about the future, is there a way that you can move parts or exist within multiple parts?

JPR: That’s a real question and it is about movement. For instance, if we start with the premise again of the eco-cosmological and the idea that everything is moving, there is also a natural and a deliberate slowing down or accelerating of things. And with that, comes the stilling, stabilizing and rendering more secure and permanent of things, a real slowing down that’s another way of thinking about appropriation. You appropriate a piece of territory and you now make it difficult for it to continue to be a space of movement, of traffic. That’s what property means, that’s why you build a fence and you say keep out, no trespassing and so forth. But we are all fundamentally trespassers. Systems have been created, such as property relations, in order to negate that fundamental trespassing or intrusion that is in fact, the very movement of existence.

Certainly, at this point in time, we live in a world that is remarkably partitioned and divided. The point has been made by a certain political theorist [Wendy Brown] that, ironically, with the fall of the Iron Curtain and the Berlin Wall, in the 30 years since, walls have gone up all over the world. And it’s probably no coincidence that at the same time that the world is facing serious issues having to do with the environment thanks to global warming, it is also wrecking itself through the enforcement of borders and the building of walls.I think these things go hand-in-hand and are not a mere historical coincidence. It is a xenophobic, nationalistic response to that uncertainty, to that force of finitude and possible extinction, to the fact that the prospect of the future is not promising. Yet there are ways to respond to that, ethically and politically, that would be about collectively thinking about this afterlife, but that’s not happening right now. What’s happening instead is the proliferation of an attitude in which every person in every country is only out for themselves, and they are going to fight this out. And so, the 1% are doing everything they possibly can to survive this, and they might, but lots of other people will not, and they already are not. As you know, the global migrant and refugee crisis is completely tied to the climate change crisis which is completely tied to the fossil fuel crisis and global war. Therefore, someone like Eyal Weitzman—and we will look at this in the seminar—with his project in forensic architecture, he can map drought, migration, oil and war, globally, and it’s the same line that runs around the globe. It’s a single zone of conflict, displacement, misery and devastation.

SP: It feels as though any of the people who want to live through this new theoretical way of thinking including this idea of non-possession, are surrounded by this way of life that makes it incredibly difficult to do so. And that if you don’t have a great enough of a collective body of people who are willing to live according to this new theoretical practice, change is not going to happen. How do you feel about that and how do you go about living this way because these are your theories?

JPR: There have been really smart, engaged and careful readers of my work who have done me the honor of responding to it, and in ways that certainly and unquestionably align themselves with it, maybe even embrace it, but who also see how, if not entirely insurmountable, nonetheless how difficult (given the current conditions and circumstances), how difficult it is to maintain this position, this stance, this commitment to things like intimacy as a relationship to the inappropriable and so forth.

I recognize that difficulty, and that’s why I do the work that I do, because the conditions today are incredibly trying and difficult, they are deeply dispiriting, depressing, and demoralizing. Yet this is all the more reason to find a source that is counter to that, that is an alternative, that is another way, because surely there are alternatives, or we would otherwise just give up. Political thinking is about thinking against the prevailing dominant order of things. And then it’s about how you’re identifying with that or not, and at what level, and in terms of what practice and form. And I believe this movement in a different direction may have begun, and while it doesn’t always end with, it does begin with the ethical—with an understanding of the close rapport we have with each other.If we can’t even begin to fathom and think about how to coexist in a way that doesn’t demand either unification, sameness, or homogenization, but at the same time doesn’t simply resort to a radical disconnect of difference, or that there’s no contact between us, then any other forthcoming political projects are impossible.

If we can’t even begin to fathom and think about how to coexist in a way that doesn’t demand either unification, sameness, or homogenization, but at the same time doesn’t simply resort to a radical disconnect of difference, or that there’s no contact between us, then any other forthcoming political projects are impossible.

First, we need to come together, and we need to be able to coexist to beareach other. And that is an ethical move. I do believe that the political begins in intimacy—and we’re not talking about sentimental love, but intimacy in proximity and closeness—that is, at the same time not a fusion but instead recognizes that intimacy as separation and distance from the other. It’s not a distance that is unbridgeable but becomes a means in which together we can understand how we share in the space that is not mine and not yours and should never be anyone’s, because it actually isn’t.

We could teach ourselves this lesson as a species; the fact that the world is not ours and do so by rendering ourselves extinct, and then we really would have proved to ourselves—too late (!)—that the world wasn’t ours, and it never was ours. Or, we can do it some other way, and we can understand that this world is not ours, that we are just trespassers passing through. Passing temporarily through this existence in this huge eco-cosmological configuration. And not be deluded into thinking that somehow, we can claim this eco-cosmos as our own.

Appropriating claims on the world have not been equivalent. Instead, the claims are of various kinds, and in their scales and intensities, some people, places, and things (and not just human but animal etc.) are suffering more than others. There is such a thing as environmental racism, and there is such a thing as climate injustice, and such things raise the question of what would be a just relationship to the world and its climate? This is why capitalism is often understood as a principal culprit, and why the thesis that has gone by the name Anthropocene has been modified so we can talk about the Capitalocene.

Capitalism is the strongest, global appropriation of the hearts, minds, species and territories. It is what believes in eternity and infinity. It fights against finitude and scarcity and the fact that things will run out. It believes that there will always be a future for it, and that it will claim that future and it’ll claim it ahead of that future, and appropriate the future and in doing so, appropriate the future for others, in the name of itself. The point is: we need to understand extinction as a force that runs through existence and understand capital as the virulent denial of that force. Capital becomes the agent for the extinction of existence because it believes that it, capital itself, can continue forever. So “the collective afterlife of things” is just as much about capitalism as it is about ecology, and that’s because capitalism has been proven to be as much a force of ecological devastation as one of financial economic destruction. Maybe those are final words?

SP: I think one of the first steps is to undo so much of how we think and how we operate.

JPR: That is always the case and you are absolutely right that has always been the case and I don’t think that’s ever not been the case. So much of it is about un-doing and un-making and un-finishing our standard ways of doing things.

SP: It’s hard because the ones that almost have to start the process or will have the biggest impact are the ones in the highest positions of power who will not surrender and make a change because that would jeopardize their positions of power.

JPR: They’re not going to do it and that’s why we have to think of another level and at a different scale. That’s what we’re talking about. We are asking about the politics of ecology and art and that relationship, and so we are talking about scale.

SP: And it feels like such a small scale that is tied to everything.

JPR: That’s it. You have to be able to diagram that scaling up, that isn’t from the small to the large but is a scaling up that is there already in what we’re calling the small or the singular. It is entirely a matter of understanding the ways in which each singularity, each thing is only a singular thing in its relationship to a multiplicity of which it is part. That relationship between the singular and the multiple is a relationship we can talk about in terms of intimacy, and one that has been perverted via a logic of unity, universality and so forth, where the one is the many, but the many is the one (like a nation). Instead, what we want to do is to keep that sense of a collective impossible in its totality—as that which cannot be totalized or generalized.

This is why in our class we read Jean-Luc Nancy’s The Equivalence of Catastrophes: After Fukushima, in which he discusses this collective or shared sense, that directly speaks to things and capitalism. Nancy argues that what we share is nothing but a common inequivalence. Or he sometimes uses the language of incommensurability, which is by definition, that which is without common measure. There must not be one single measure by which we accord value to anything. What capitalism —and now Nancy is drawing from Marx—has done is to institute a logic of general equivalence and the instrument of that general equivalence is measured and instituted as money. That’s the common denominator. That’s how we know if something is valuable, and also how to treat it, and how it is able to circulate and be in the world. But, of course, that logic of general equivalence, which is the logic of capitalism, has become a mentality and rationality by which everything is measured. And what Nancy is saying is that now we are at the point that we can (unfortunately) talk about the equivalence of catastrophes, such that no matter what the problem might be, it seems as though all catastrophes are either reduced to the same level, or measured according to a scale that is in no way ever going to get at the pain and suffering experienced in those particular singular catastrophes. Instead, this calculative logic will chalk it up to some kind of table of costs, such that there’s a leveling. If we return to the earlier part of our conversation on disaster, how is it that art can present the catastrophe in such a way that it doesn’t operate with a sense that it has a single general principle in which to measure that disaster?

Nancy says we need to think and act in terms of an equality, if we’re going to talk about equality what we have and are striving for is an equality of inequivalence. That’s what makes us equal. What makes us equal to each other is that we are inequivalent to each other. There is equivalence, and he is trying to separate out and distinguish equality from equivalence. We sometimes think these terms are interchangeable, but Nancy is pointing out that equivalence pertains to a measure, including a general measure of value, whereas equality, the only real equality in which we can think of as a shared collective equality, lies in a common inequivalence. That is: the lack of common measure. To bring it back to your question, I would say that oppression and marginalization are the means by which that inequivalence is no longer taken to be the only source or condition of equality. When that inequivalence is no longer considered the only thing by which we can think about equality, but instead is used to institute and perpetuate all kinds of inequity.

We need to understand global financial capitalism as an ecological force of extinction. One that has produced an equivalence of catastrophes through the illogic of general equivalence. The latter is opposite to a deeply ethical insight, the one that affirms that our equality lies in our inequivalence to each other and to the world.

Please feel free to share: